Mending Broken Pieces

Cracked screens and shattered smartphones. The sleek aesthetics and delicate materiality of technological devices renders broken as trash. Forces that encourage continued expansion resist strategies of repair and new shiny objects chase the illusion of perfection. What if we instead embraced the imperfections of devices as they age? How might we develop repair techniques that emphasize repair as part of the beauty of an object?

-

chevron_rightKintsugi

Kintsugi (“golden joinery"), also known as Kintsukuroi ("golden repair"), is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. The resulting pieces are believed to have significant beauty and are often considered more valuable than the original. The “broken-ness” of the objects is celebrated and their usability extended beyond that of its original use. How might we resist the temptations of planned obsolescence and the fragility of technological devices to instead embrace the damage and repair that occurs through the life of these objects?

-

chevron_rightWabi-Sabi

Wabi-sabi is centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. It is an aesthetic tradition that is sometimes described as one of beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete". It is derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence, specifically impermanence, suffering and emptiness or absence of self-nature. Our technological devices have been designed based on ideals that are rooted in precision and perfection. What if they were instead driven by imperfection and assumed impermanence?

Instead of planned obsolescence or rapid replacement, devices are developed to encourage repair and slow replacement. Innovation focuses on extending the life of devices through material selection and repair techniques.

The sleek, delicate aesthetic that has permeated design has promoted the “new shiny object” and encouraged shortened life spans. The “new shiny object” is replaced with the “the beautifully flawed object”. Damage and repair are traces of the story of objects. Attention is given to treating repair as an aesthetic, highlighting it and encouraging imperfection.

Gee's Patchwork

Gee’s bend is a small community in Alabama. Most of the inhabitants of this remote community “are mostly descendants of slaves, and for generations they worked the fields belonging to the local Pettway plantation.” The women of Gee’s bend have produced patchwork quilts beginning as far back as the mid-nineteenth century. Few other places have “works been found by three and sometimes four generations of women in the same family, or works that bear witness to visual conversations among community quilting groups and lineages.” Because of the isolation of their location quilters used whatever materials were on hand, often recycling from old clothing and textiles. Could we think about e-waste as “materials on hand”? Can we develop connection systems that allow us to reuse and repurpose discarded computing parts, quilting them together in new configurations?

-

chevron_rightPatchwork Quilting

Patchwork quilts include “a top layer that consist of pieces of fabric sewn together to form a design.” Originally, discarded or left-over scraps were accumulated over time and attached to each other to make larger blankets. Quilting has historically been an important practice for African-American women. “The voices of black women are stitched within their quilts.” The technique allowed black women to make large textiles with limited materials, supported social communities, and even carried coded communication.

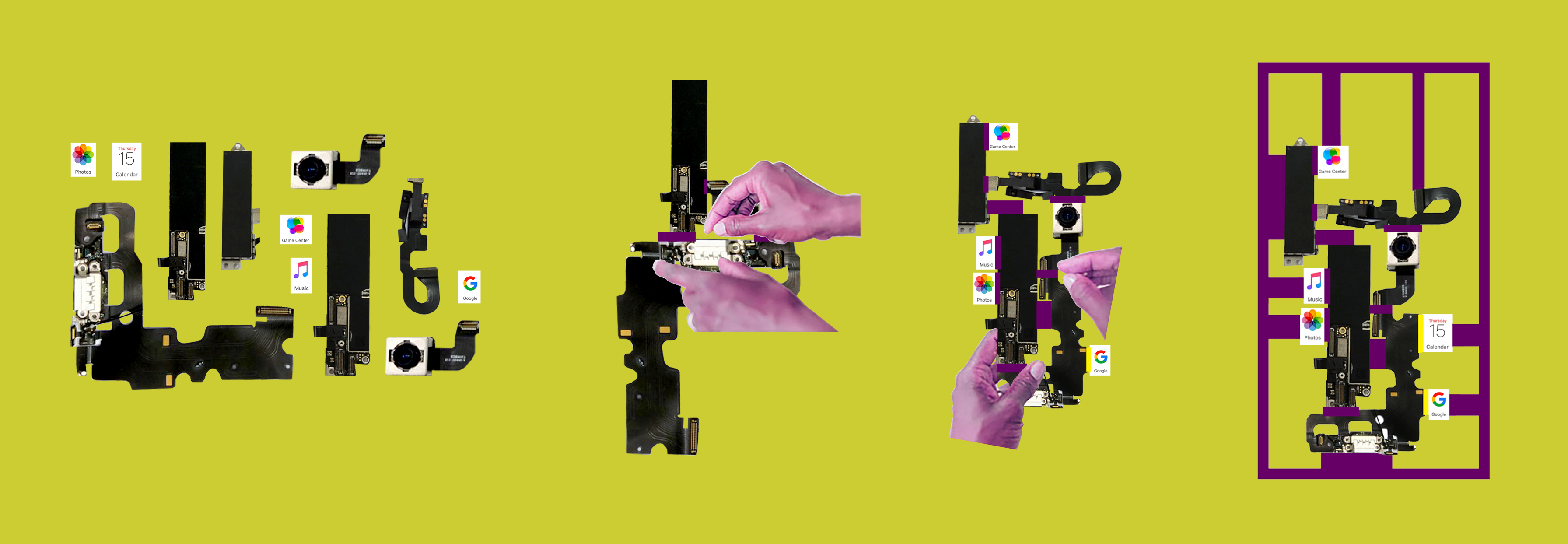

E-waste is not waste at all. Instead it is scrap material available for new creations. Functioning components do not have to be discarded along with nonrepairable ones.

Design prioritizes deconstruction and disassembly over black box strategies that are inaccessible to users. New configurations of technological parts can be achieved. No longer are devices limited by previous forms of “phone” or “computer”. Instead they can be reformed with scaffolds of any shape.